There’s a memorable moment in the film Silence of the Lambs when the FBI agent Clarice Starling enters the house where the serial killer Buffalo Bill is holding Catherine Martin hostage. As Clarice bursts through the door, her gun drawn, her arm shaking, she calls out to Catherine in a quavering voice: “FBI! You’re safe!” That line, I recall, got a huge laugh when I saw the film on its release nearly thirty years ago. We laughed, as the filmmakers intended, because of the absurdity of Clarice’s assurance. As long as Buffalo Bill was alive on the premises, neither Catherine nor Clarice could possibly be “safe”.

I thought about that scene this morning when I set about to explain why, in teaching EMBER to students with a likely history of trauma, we never use the term “safe”. For some of our trainee teachers, this comes as a surprise. There is much talk in the media now about creating “safe spaces” in universities for class discussion or “safe containers” in therapy for difficult feelings. Psychologists, for their part, recognize the sense of “safety” as fundamental for human wellbeing: it is second only to food, water, and shelter on Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. We all want and need to feel safe. So why not use the word?

The problem lies with the term’s connotations. Safety is an all-or-nothing concept. You are either safe or you’re not. You can’t be a little bit safe any more than you can be a little bit pregnant. The term “safe” has a finality about it. Once you’re safe, that’s it. “You’re safe” in baseball once you’ve tagged the base and the umpire flags that you have arrived.

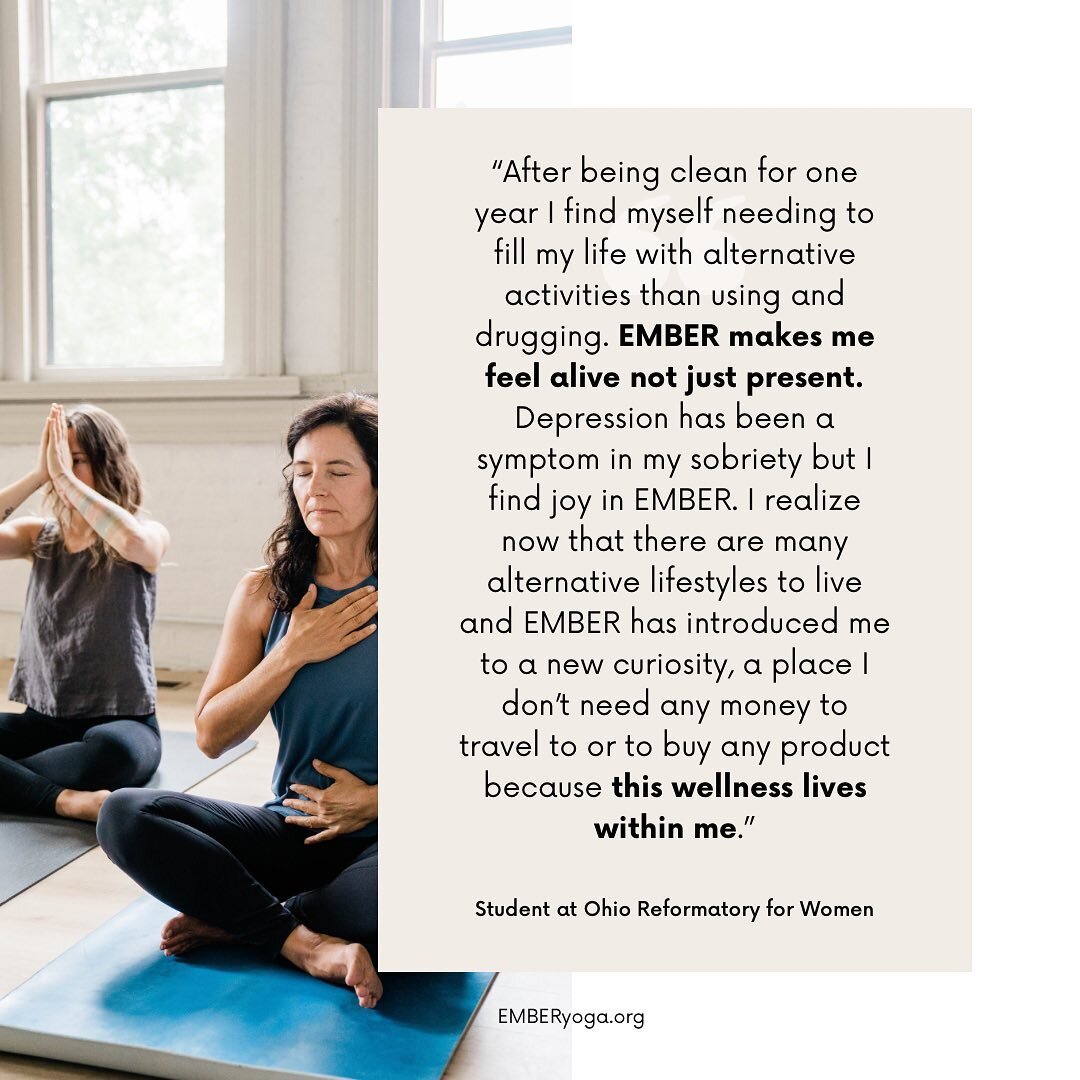

Feeling safe, in other words, depends on an inner confidence that you will remain free from harm. For many of the students we teach, that confidence is often, with reason, hard to attain. Many of them live in institutional settings (prisons, jails, treatment facilities) where life is often chaotic and where they have little freedom of movement. Others live with limited means in households or neighborhoods where physical or emotional violence is a perennial threat. Almost all of them carry habits of hyper-vigilance cultivated for their survival over years of exposure to adverse conditions. To invite them to feel safe – to find a “safe space” even in their imagination – is to set the bar well out of their reach. Exhortations to feel “safe” can too readily invoke exactly the opposite: feelings of embattlement, anxiety, and fear.

It is impossible to feel “safe” without knowing what safety actually feels like. Safety, in other words, is composed of sensations: a settling or loosening or softening in the body. Those sensations can take time to get used to. In EMBER, that is where we begin: not with “safety”, but with physical sensations of ease. Instead of urging our students to feel safe on command, we invite them to identify feelings of ease in their body.

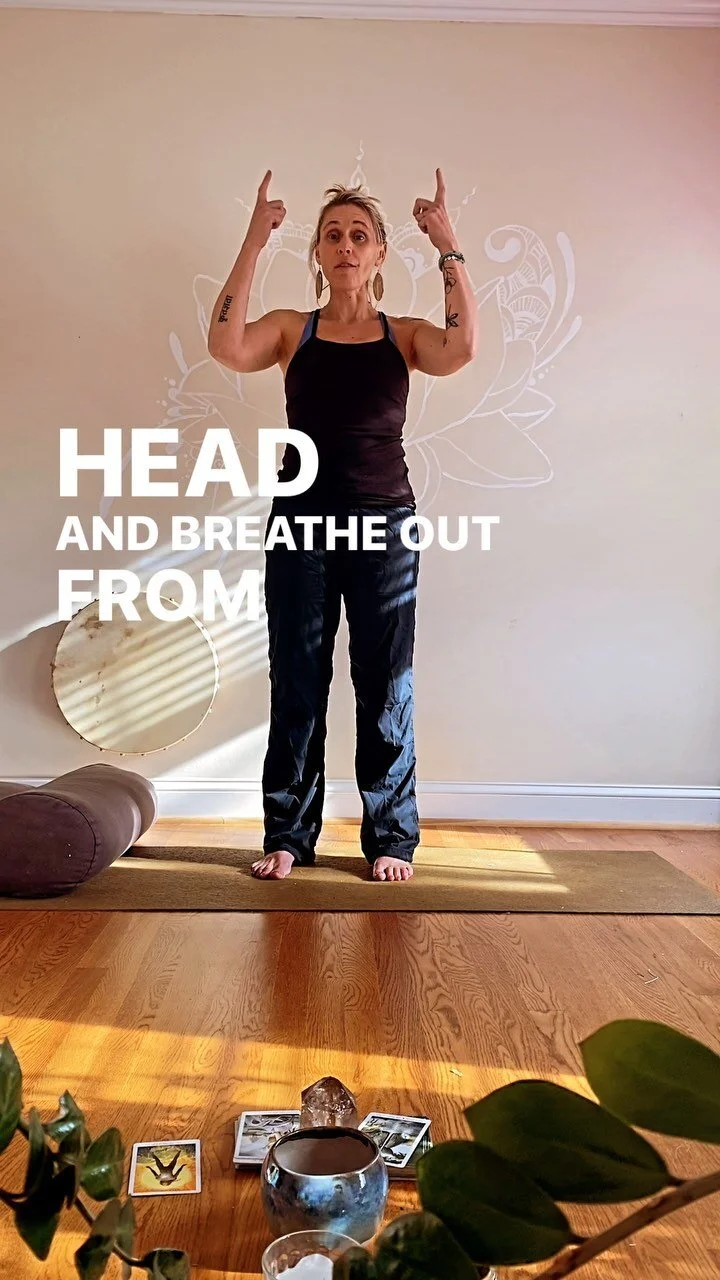

At first, the easiest way for you to identify those sensations might be to create them: tensing up your shoulder muscles and letting them go and experiencing them grow loose and heavy, or letting your tongue be loose in your mouth and feeling any easing or softening in the jaw. In the first weeks of EMBER, we teach a tense-and-release body scan meditation where we sequentially clench and release the big muscle groups of the body, focusing on the sensations that follow, feeling the muscles of the legs and arms softening, settling, and letting go.

From there, you can move to finding ease where it already exists, by following the breath, or more specifically the exhalation. When you inhale, you might notice a slight feeling of effort as the diaphragm tightens, but when you exhale, the diaphragm releases, and with that comes a sensation of softening and settling. You don’t have to make this happen. Those sensations will come on their own.

Starting with feelings of ease in the body is a first step toward a feeling of safety. What matters is that it is an attainable step, with its focus on physical sensations that anyone can either create or find. With time, we can build upon those sensations to create a personal, reliable feeling of refuge. But at the outset, those physical sensations provide critical first steps toward that quiet inner sense of assurance, something anyone can tap into, even when abstract concepts like “safety” feel very far away.